A Very Curious Flag

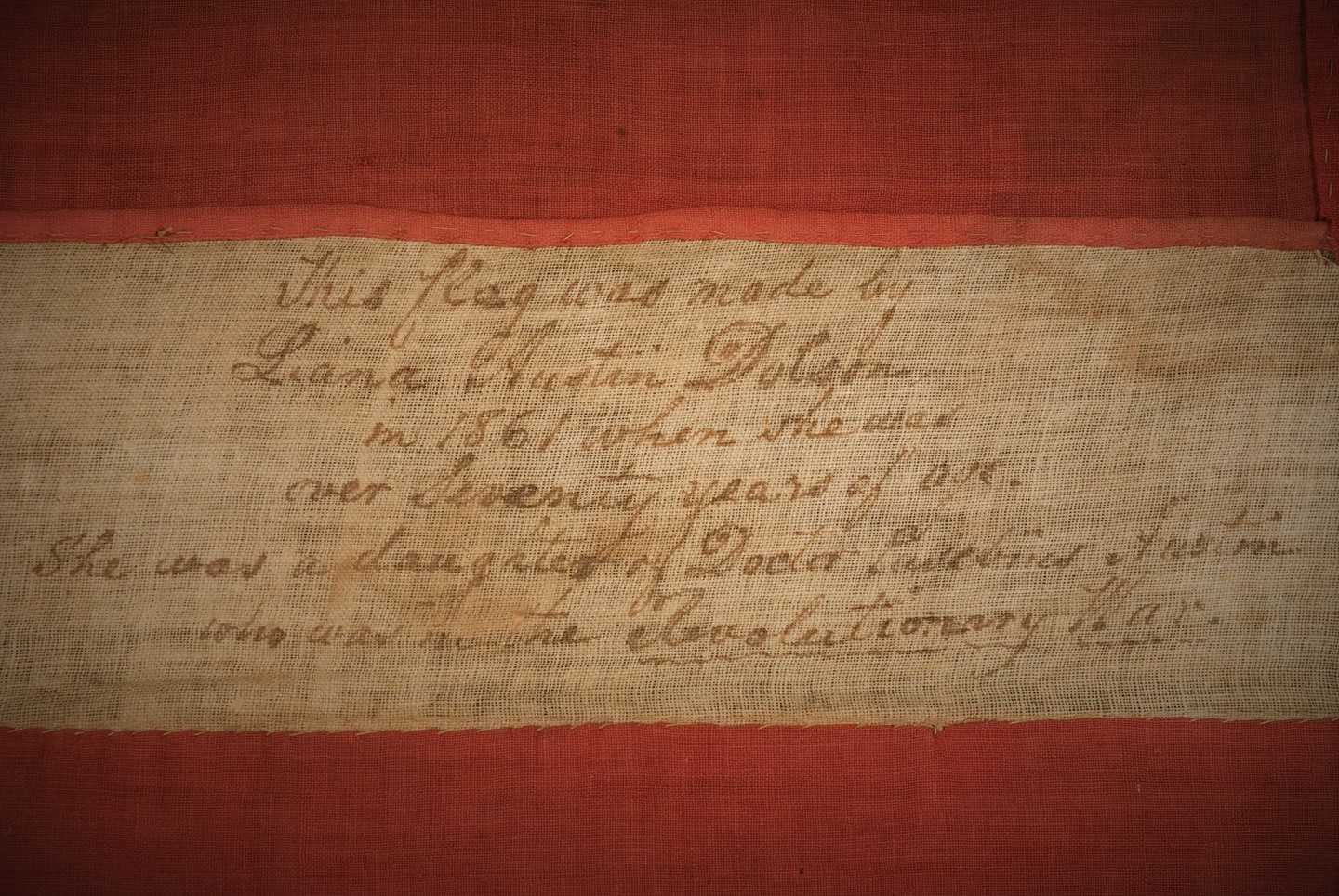

The Neversink Valley Museum has a very interesting flag. Its 1861 American flag is a perplexing bit of history. On the canton where the flag’s stars reside, the front side has 21 stars in a starburst or “exploding galaxy” pattern and the reverse has 13 arranged in an “X” design, also known as a “St. Andrew’s cross”. The United States did, in fact, have 34 states in 1861 when Kansas was admitted to the union in January of that year. The 34 star American flag appeared on July 4th as required by the Flag Act of 1818. A note written on one of the flag’s white stripes reads: “This flag was made by Liana Austin Dolson in 1861 when she was over seventy years of age. She was a daughter of Doctor Eusebius Austin who was in the Revolutionary War.” The question is what the reason was for the creation of this unique flag. Could it have been a “secessionist flag” meant to honor the creation of the Confederacy as suggested by the late Howard Madaus, a well-known U. S. flag scholar?

The answer to the question of the Dolson flag lies in understanding the historic context in which the flag was created. In 1861, before the horrors of the war were realized in the spring of the following year, the toll of the Civil War had not yet sunk in and the draft riots were yet to happen. The Battle of Shiloh would take place in April, 1862 and would claim over 23,000 dead on the battlefield. News of the battle would spread quickly and the event would be a turning point in the perception of the war. It would be apparent from that point on that the war would not quickly be over and that enormous casualties would be suffered by both sides.

In the relatively calm atmosphere of 1861 the polemical content of the flag becomes clear. There was a patriotic fervor in New York State in 1861 that started to evaporate towards the end of the following year. Civil War historian and expert on life on the Civil War home front, Juanita Leisch Jensen, interprets the flag as a reference to the 13 original states of the War of Independence. This makes sense. Mrs. Dolson was born October 18, 1786 and would have been brought up in a household full of revolutionary fervor. It seems that Mrs. Dolson was raised in one patriotic family and later married into another. She took Theophilus Dolson as her husband and had three sons and a daughter by him according to genealogist Nancy Conod of the Minisink Valley Historical Society.

The Dolson family of Orange County had at least three of their number who served in the illustrious 124th New York Volunteer Infantry, the “Orange Blossoms”, according to The History of the One Hundred and Twenty-Fourth Regiment published after the war in 1877 by Charles H. Weygant who had served as a Captain in the regiment. Two of the men, William and Jesseniah served in Company D organized at Warwick and the other, Theophilus from Wallkill, served in Company E. Theophilus enlisted as an 18-year old corporal who later rose to become first sergeant. (As an aside, he became a well-know and highly respected conductor on the Erie Railroad after returning home from the war and retired in 1913 following nearly a half-century of service to the railroad company.) Contemporary records reveal that Liana’s brother-in-law, her husband’s brother Frederick, was Theophilus’ grandfather making Mrs. Dolson his great-aunt. (Theophilus also had the same name as her husband as well as a number of other male Dolsons in Orange County). The three Dolson men had signed up for the 124th even after it was clear that the war would be brutal. Patriotic fervor must have been high in the Dolson family.

According to Bob Luddy, former president of the Brandy Station Foundation in Culpepper County, Virginia, on June 9, 1863 the Orange Blossoms fought at the Battle of Brandy Station, a predominantly cavalry engagement. The Civil War Preservation Trust characterizes this battle, also called the Battle of Fleetwood Hill or the Battle of Beverley’s Ford in the history books, as the largest engagement involving cavalry to have ever taken place on American soil. The beginning of General Lee’s Gettysburg Campaign is marked by this battle. It was also a turning point in the fortunes of the Union cavalry. As the Richmond Examiner lamented after the battle, the Union cavalry had bested their Confederate counterparts that day.Clark B. Hall, a Civil War expert and authority on the Battle of Brandy Station, even characterizes the battle as the beginning of the end of the southern cause.

The 124th had an important role in the Battle of Brandy Station. Two of the Dolsons seem to have missed this battle because William had been discharged on April 11 due to illness and Jesseniah was probably still recovering from a wound received at Chancellorsville on May 3rd. However, Theophilus did bear witness as this important engagement unfolded. How appropriate that a member of a staunch Union family should have played a part at the beginning of the end of the Confederacy. The Dolsons certainly were active participants in the Union cause. Liana Austin Dolson must have been proud.

The message that the flag was most likely meant to convey in late 1861 was of support for the Union, not the Confederacy. The Orange Blossom Regiment left Goshen in late summer 1862 headed for battle. At that time there were no illusions that the war would be over quickly with minimal bloodshed. The Dolsons certainly seem committed to the Union cause. This may be the clue that the flag was a “home front flag” meant to display patriotic pride and to counter the sentiments expressed by the Peace Democrats or Copperheads as they were also known. These home front flags were usually displayed in a window or hung on a wall as a tribute to the local young men serving in the army. Furthermore, Juanita Leisch Jensen also notes that other factors indicate that the flag was a home front flag that stayed home. These include such significant observations that:

- •

Overall Front Before Treatment - •Rather than cutting the stars of the Confederate states from the American flag, as some Union patriots did, Mrs. Dolson seems to have chosen to focus on the message of the American Revolution, of which she appears to have been quite proud. It is also important to note that the Austins and Dolsons (and Woods from the side of her mother, Abigail Wood Austin) were old and venerable Orange County families. They were pioneers to the area and were prominent during the colonial and revolutionary periods. The Dolsons trace their lineage back to Captain Jan Gerritsen Van Dalsen who arrived in New Amsterdam in the mid-17th century from Holland. Mrs. Dolson’s father, Eusebius Austin, was a prominent physician and surgeon. Earlier, he had served during the War of Independence at West Point and Morristown, New Jersey and is said to have been at Valley Forge with George Washington in 1778. It’s hard to imagine someone from the North with such an illustrious background supporting the dissolution of the Union.

The notion of a 13 state Confederacy was not clear during most of 1861 and the South, itself, hadn’t settled on the matter until the end of November of that year when it added two stars to the 11 star Confederate National flag. The new stars represented Missouri and Kentucky, both of whom had competing Union and Confederate state governments. Mrs. Dolson in Orange County, New York would have been hard pressed during most of 1861 to believe that the Confederacy consisted of 13 states. When the issue was finally resolved the year was almost over. It would have taken time for the news to reach upstate New York and Mrs. Dolson would have had to work at a stiff pace to complete the flag before the year was out. This all makes it seem highly unlikely that the 13 stars were meant to represent the states of the Confederacy.

In late 1862 with the growth of the Copperhead movement and the anti-war emotion that went with it, a Secessionist or similar interpretation might seem appropriate. The flag might make some sense as a protest against the war had it been stitched then or in 1863 or even mid-1864 when Copperheadism reached its peak. Perhaps Mrs. Dolson could have been a Copperhead who didn’t support the war or who was even sympathetic to the South. But the flag was made in 1861 when strong anti-war sentiment had not yet taken hold widely and Mrs. Dolson was very likely a staunch American patriot. On the other hand, the configuration of the 13 stars is in the shape of an “X” which is the same way that the stars are displayed on the Confederate Battle flag. Could this belie Mrs. Dolson’s support for the Union? The Battle flag was designed in September 1861 and wasn’t actually flown in battle until December 1861. There is little chance that Mrs. Dolson could have known of this configuration and sewed her flag before the year was out.

So, why did Mrs. Dolson place the 13 stars on the reverse of the canton in an “X” configuration? The Confederate National flag had its stars arranged in a circle, just as the first American flag had. Did Mrs. Dolson deliberately avoid the circle of the “Betsey Ross” flag because the Confederate National flag used the same configuration? This is highly unlikely since the Confederate flag for most of 1861 had 11, not 13 stars. Using a 13 star circle would have sent an unmistakable pro-Union message but Mrs. Dolson chose not to. Did she pick an “X” because it was the opposite of the circle used in the Confederate National flag? This is rather farfetched since the “Betsy Ross” flag also had its stars in a circle. Perhaps the answer is really quite straightforward. Mrs. Dolson might have used the “X” pattern on the reverse canton simply because it mirrored the “X” pattern in the starburst on the other side. It’s even possible that she used the obverse pattern to lay out the position of the stars on the reverse. It’s highly likely that Mrs. Dolson wasn’t sending any message at all with her “X” but was merely working from some design concept she had in mind.

Of course there were pro-slavery advocates and Confederate sympathizers in antebellum New York. Up to the late 18th century New York had the greatest number of slaves outside of the South. Moreover, the population of the Hudson Valley, especially its eastern shore, had the largest proportion of slaves in the state. This doesn’t mean that Mrs. Dolson likely was a secessionist. Since her mother was buried in the hamlet of New Hampton in central Orange County, and Mrs. Dolson lived in the Town of Wallkill only a few miles away, we believe that Mrs. Dolson was not raised in a major slave-owning area. An observer notes that, at the time in central Orange County, “public sentiment, while not openly expressed, was largely with the abolitionists”. So, regardless of the presence of a significant pro-slavery faction in the Hudson Valley, all the evidence points to Mrs. Dolson being a devoted defender of the Union.

Maybe Mrs. Dolson had found a unique way to honor her Revolutionary roots and to point out that all the states of the Union stand on a foundation built by the original 13. That the southern states wanted to leave the Union might have seemed a travesty to her and the flag she created may be her way of expressing rejection of their act of rebellion. Certainly, her patriotism is reflected in the three young Dolsons who felt so strongly about preserving the Union that they signed up for duty even after the brutality of the war was widely known.

We’ll probably never know Mrs. Dolson’s intent in making her unique flag. What we do know of her family and background as well as the events of 1861 and 1862 all suggest that her flag was meant as a patriotic gesture and not to take issue with the Union’s armed efforts to bring the southern states back into the fold. It just seems unreasonable that the Dolson flag had any secessionist intent. Everything seems to support an interpretation that the flag was created by a woman with strong Union sympathies.

Ideally, history museums preserve material culture, artifacts, and integrate and interpret the history represented by them.This is important and makes a history museum much more than simply a museum of local history. History museums should integrate the history reflected in local setting with the wider forces that influenced the local life being portrayed. They should interpret local history in the context of this integration. Things that may not make too much sense if just seen locally take on a more coherent meaning when viewed as part of a larger, more global whole. This is the story of the Dolson flag. At the very least, as an educational device, the flag helps contrast the change of sentiment from 1861 to late 1862 in our area as well as across the entire nation.

Short Link: