Irish Glass Makers of Ellenville

Stories of the rowdiness of the Irish construction gangs building the D&H Canal are legendary. These owe more to the cultural mythology of the nineteenth century than to actual fact. Whilst there are well-documented instances of serious disorder, this is a far cry from the picture that was painted of disorderly drunkards. In fact, many Irish immigrants were law-abiding contributors to their new homeland.

The D&H Canal was built from 1825 through 1828. Construction was also continuous between 1842 and 1851 during the various canal enlargement projects. From the beginning, local workers could scarcely fill the needs of the D&H Canal Company. Advertisements were placed in newspapers throughout Pennsylvania, New York and Connecticut. Many Irish workers responded to these early calls for laborers.

Owing to the establishment of a significant Irish population along the canal corridor, many ethnic Irish knew something about the area. Successive potato crop failures between 1845 and 1849 set the stage for the Great Irish Famine and the resulting surge in Irish emigration during the 1845-1855 “Famine decade”. The opportunities afforded by the decade-long expansion of the D&H Canal coincided with the imperative many Irish felt to flee the hardships of the Irish famine.

The census of 1860 is filled with many local Irish surnames. We find numerous people in the census born in Ireland with names like McQuick, McMahon, McCarron, O’Brien, Reilly, Kinnie and O’Boyle. Perhaps one of the most famous is Mary Casey who ran the Pie Shop at Lock 51. She was known far and wide for her skill in making rice pies. She also made small treats for children who came by on the canal boats.

Besides unskilled laborers, many of the Irish immigrants who came to the area were skilled artisans. We know that Irish stonemasons helped build canal locks and aqueducts. We also know that others of their countrymen were skilled glass workers.

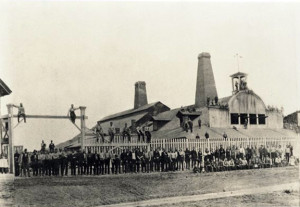

The Ellenville Glass Company was established in 1836 by a group of glassmakers from Connecticut. Its location was chosen because it had an abundant supply of wood fuel nearby and was close to the D&H Canal. The company had two slips on the canal from which it received raw materials and shipped finished products. Soda ash came from England by way of Boston soap makers. Sand was shipped from New Jersey and limestone from Ohio. Bottles were shipped westward via the D&H Canal, Hudson River and the Erie Canal.

In October 1837 the company started making bottles using as much as 10,000 cords of wood yearly. The company owned large tracts of land that it divided into 50-acre lots it then sold off. The new settlers cleared the land and sold the wood to the glassworks to pay for the land.

In 1859, due to a diminished supply of wood fuel, the company switched to coal in its blast furnace. There was a ready supply of coal shipped on 125-ton D&H Canal coal boats from the coalfields of Pennsylvania. This change was made possible by a new technology that fed pre-heated air into the furnace thereby avoiding a strong draft which would have broken the clay pots where the raw materials were melted. At its peak the glassworks consumed about 4,000 tons a year.

Reorganized in 1866 under the name of Ellenville Glass Works, the company went on to become one of the largest operations of its kind in the United States. In its heyday it had annual sales of $400,000, produced 18,000 carboys and 56,000 demijohns and employed over 500 workers. Many women and children worked covering bottles with woven willow twigs raised on the company’s “Willow Lot” to make carboys and demijohns.

A good number of the company’s employees came to this country from England, Ireland and Germany. In fact, Ellenville had so many Irish and Germans that each congregation had its own Catholic church. Most of the willow twig weavers were German. The original glass blowers came from the New York Glass Company when it went out of business. Most of these blowers originally came from England and included a number of Irishmen.

Ireland had a long tradition of glassmaking and a significant population of skilled glass workers. However, little has been written about the Irish who came to work at the Ellenville Glass Company. Nevertheless, some information is still available today.

We do know that John McMullen originally learned his trade in Dublin and came to Ellenville in 1837 as a foreman at the glass works. He had a large family and most of his sons went on to become glass blowers. We also know that John Connolly was born in Ireland and learned glassblowing in Ellenville. William Murphy and James Sweeney also came from Ireland and learned their trade at the factory.

To learn more about the fascinating story of the Ellenville Glass Company a visit to the Terwilliger House Museum in Ellenville is a must. The Museum’s permanent collection includes many examples of the glassware manufactured in Ellenville. These include bottles, fruit jars, insulators for telegraph poles, glass canes, paperweights and ornamental objects called “whimsies” or Collectors Glass as well as carboys and demijohns (glass bottles protected by wicker basketwork).

Copyright 2006 by Stephen Skye

Short Link: