Stephen Crane and D.W. Griffith

Author Stephen Crane and film maker D. W. Griffith were prominent figures in American arts at about the same time. Both had connections to the Tri-State area and were in the area within a few years of each other. Both were pioneers in what cultural historians today call American Modernism and were part of the reaction against Romanticism that occurred during the later 19th century. Both tried to depict the Civil War realistically in their signature works and dealt with the issue of race relations in America. It can be useful when trying to understand an historic figure to compare that person with someone of comparable circumstance and stature. In this case, looking at Stephen Crane and D. W. Griffith can provide powerful insights into Griffith and his work.

Racism has always been a significant feature of American society. Following the collapse of Reconstruction in the South in 1877 it took on a new, malevolent tone. The end of Reconstruction saw the rise of the Klu Klux Klan. Lynchings became part of the American social landscape as well. This was not restricted just to the South. Port Jervis witnessed a lynching in 1892. The Tri-States area also had a significant Klan following well into the 20th century. For example, in 1922 a large cross and three large K’s were set ablaze atop Point Peter high above the city. How Crane and Griffith responded around the turn of the century to this dark chapter of America’s history is very telling.

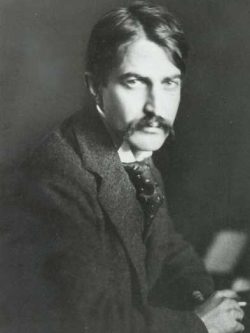

Stephen Cra ne moved to Port Jervis around 1878 with his family as a child of 6 and lived there throughout his youth. Though he left Port Jervis when he was grown, he frequently returned to visit family and friends up to the time of his death in 1900. He was an avid sportsman and loved to fish and hunt during his visits to the area. His father was a Methodist minister; perhaps this explains why he had an enlightened view of race relations. He wrote his signature work, The Red Badge of Courage, in 1895 and his novella Monster in 1898. The former revolved around the Civil War and the latter dealt with an African-American character disfigured in a chemical fire at the end of the 19th century.

ne moved to Port Jervis around 1878 with his family as a child of 6 and lived there throughout his youth. Though he left Port Jervis when he was grown, he frequently returned to visit family and friends up to the time of his death in 1900. He was an avid sportsman and loved to fish and hunt during his visits to the area. His father was a Methodist minister; perhaps this explains why he had an enlightened view of race relations. He wrote his signature work, The Red Badge of Courage, in 1895 and his novella Monster in 1898. The former revolved around the Civil War and the latter dealt with an African-American character disfigured in a chemical fire at the end of the 19th century.

A credible case has been made by a number of scholars that Monster was modeled on the 1892 lynching in Port Jervis of Robert Lewis, an African-American man accused of rape. Though in Asbury Park, New Jersey at the time, Crane would have been aware of the specifics of the event, especially since his brother, “Judge” William Crane, attempted to stop the lynching. The parallels of the novella with the event and the notoriety of Lewis’ murder support a powerful case for linking Crane’s work to the lynching. Just as it was the mob that was the monster in the lynching, in the novella it is the townsfolk who torment the disfigured black man where one will find the real monster. In Monster Crane displays a sensitivity and understanding of the plight of the African-American in contemporary America.

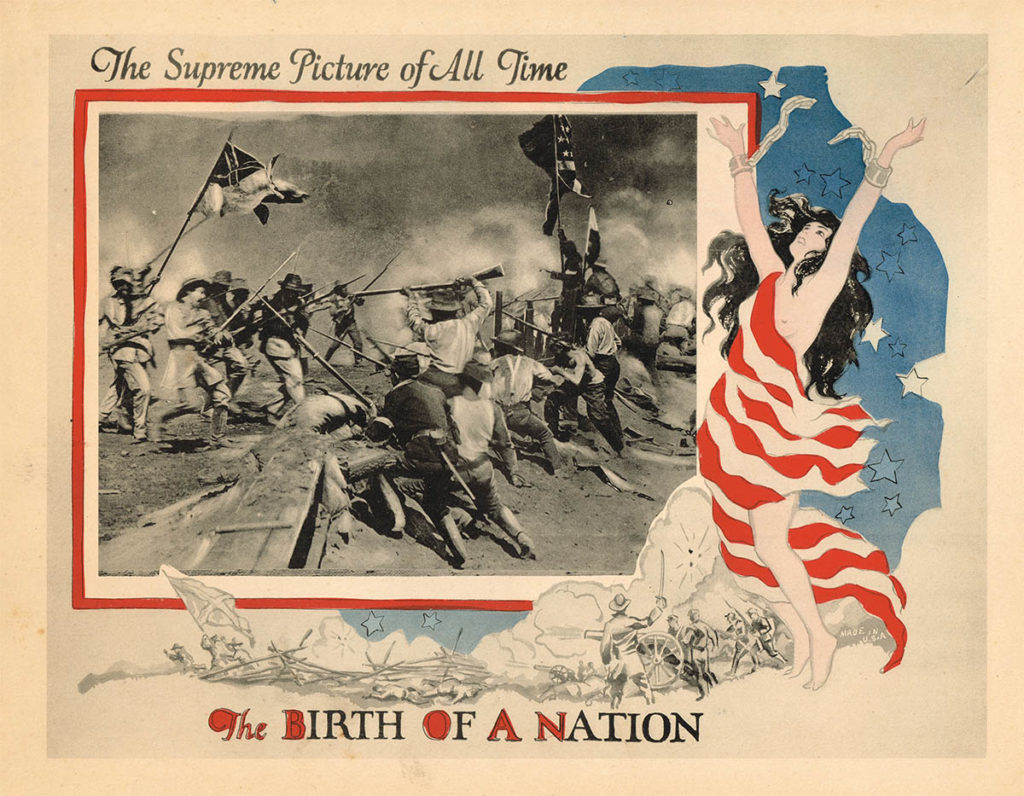

D. W. Griffith was born in Kentucky in 1875. His father was a former Colonel in the Confederate Army and a war hero. This helps explain his views on the Civil War and African-Americans. He came to Cuddebackville because of the rugged scenery of the Neversink River valley which served as the backdrop for many of the works he produced there. He made films in Cuddebackville from 1909 through 1912 and was familiar with the area. It was in Cuddebackville that Griffith developed a significant part of his repertoire of cinematic techniques. After his Cuddebackville period, Griffith produced his landmark work, Birth of a Nation in 1915 and his most expensive and ambitious film Intolerance the year after. His 1915 film dealt with the Civil War and the rise of the Klu Klux Klan and Intolerance was a rebuttal to the criticism that he received after Birth of a Nation that he was a racist.

D. W. Griffith was born in Kentucky in 1875. His father was a former Colonel in the Confederate Army and a war hero. This helps explain his views on the Civil War and African-Americans. He came to Cuddebackville because of the rugged scenery of the Neversink River valley which served as the backdrop for many of the works he produced there. He made films in Cuddebackville from 1909 through 1912 and was familiar with the area. It was in Cuddebackville that Griffith developed a significant part of his repertoire of cinematic techniques. After his Cuddebackville period, Griffith produced his landmark work, Birth of a Nation in 1915 and his most expensive and ambitious film Intolerance the year after. His 1915 film dealt with the Civil War and the rise of the Klu Klux Klan and Intolerance was a rebuttal to the criticism that he received after Birth of a Nation that he was a racist.

Birth of a Nation depicts African-Americans in a very negative light and justified the rise of the modern Klan to protect white interests, especially white womanhood. Though a masterpiece of the art of filmmaking, the film is blatantly racist and depicts a lynching as a noble act in one of its scenes. It explicitly portrays the Klan as heroes and African-Americans as inferiors. It depicts slavery as benign and even ended up being used as a recruiting tool by the Klan.

Reacting to accusations of racism after the premier of Birth of a Nation, Griffith went on to produce Intolerance in order to refute that charge. The film cost about two million dollars to make and was not a commercial success. One of the greatest films of the silent film period, it contains four stories from various eras of history that illustrate bigotry, discrimination and injustice. It is interesting to note, however, that nowhere in the film is any person of color portrayed.

Though the views expressed by Birth of a Nation were commonplace in early 20th century America, that does not justify its virulent racism. Stephen Crane was a contemporary of Griffith but treated race relations much differently. Taking Monster as a parable of a lynching, we can see that Crane clearly shows the lynch mob as villain. Compare this with the way Griffith treats his mob in his lynching scene. There, the mob avenges the death of a white woman who would rather jump to her death than be violated by an African-American.

Both Crane and Griffith advanced the craft of their creative fields and helped perfect new devices in order to increase the realism of their works. The Red Badge of Courage and Birth of a Nation are masterpieces of the early days of American Modernism. However, there the similarities end. The tone and content of each work differ greatly. One is sympathetic to the plight of African-Americans; the other portrays them as rogues and thugs. This difference in the way they depict African-Americans lies at the heart of the way we should view these two great narrators of the American scene.

Perhaps the difference in their world views is due to their different backgrounds. One was a minister’s son while the other was the son of a Confederate officer. Crane’s upbringing probably made him sympathetic to the African-American cause, whereas Griffith would have had to overcome the values with which he was raised. The point is that he did not transcend the racist legacy of his childhood and never even realized its depth. Therein lays our disappointment with him. Our backgrounds need not invariably define who we are. We do have a choice in the values we uphold.

Copyright 2008 by Stephen Skye

Short Link: