Black Diamonds and the D&H Canal

During the early 1800’s, New York and other cities were dependent on wood and imported bituminous (soft) coal for their energy needs. As forests became depleted and shipments of bituminous coal were restricted during the War of 1812, these cities needed a new energy source for their growing industrial needs.

During the early 1800’s, New York and other cities were dependent on wood and imported bituminous (soft) coal for their energy needs. As forests became depleted and shipments of bituminous coal were restricted during the War of 1812, these cities needed a new energy source for their growing industrial needs.

From Pennsylvania to New York City

Two brothers from Philadelphia, Maurice and William Wurts, owned land in Pennsylvania rich in anthracite coal, also known as hard coal or black diamonds. The Wurts brothers believed that this anthracite coal would help fill New York City’s energy needs, but they needed an efficient way of transporting their coal. A CANAL, or man-made waterway, was the best form of transportation at that time. Even though canals were more expensive to build than roads, once built, large quantities of goods could be transported more quickly and easily by a canal. ONE HUNDRED TONS in a canal boat could be pulled by two horses faster then they could pull ONE TON in a wagon over land.

Much of the canal was built through wilderness areas, using only picks, shovels, blasting powder and the backbreaking labor of thousands of men. In the spring of 1826 alone, 2,500 men and 200 teams of horses were working on the section of canal between Cuddebackville and Kingston. John Jervis and Benjamin Wright, among others who helped build the Erie Canal which was completed in 1825, came here to build the D&H. The canal was dug four feet deep and included numerous basins, dams, feeder canals, aqueducts, and one hundred and eight locks. Started in 1825, it was completed in less than three years.

Canal Locks & Aqueducts

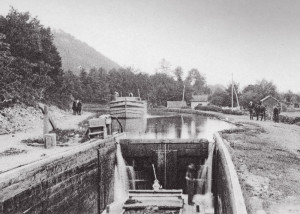

There were 108 locks on the D&H, with average elevation changes of between eight and twelve feet for each lock. Early canal locks were the balance beam type, seventy-six feet long and nine feet wide, and could accommodate twenty-five to thirty-ton boats.

Aqueducts carried the canal over rivers or other waterways. While there were many very small aqueducts along the canal route, originally there were only two major aqueducts over the Neversink River and Rondout Creek. During an extensive enlargement of the canal between 1847 and 1851, four new aqueducts were built. The engineer of all four aqueducts was John A. Roebling (1806 – 1869), who was also the builder of the Brooklyn Bridge. He used wire rope in all of his bridges and aqueducts, which assured strength, rigidity, and stability against the forces of nature and the heavy loads carried across the aqueduct.

Canal Boats

Individuals bought a company boat and paid for it through installments, with interest. This payment was deducted from the money they received each trip for the freight they carried. The person who owned the boat was responsible for the boat, its equipment, personnel, and motive power.

The earliest boats carried only ten tons of coal because the canal could not hold the expected four feet of water needed to float more weight. It was not until 1840 that four feet of water could be maintained, which permitted the use of thirty-ton boats. By 1842, the canal was deepened to five feet, which allowed forty-ton boats to ply the canal. These boats cost the boatmen $400. The most extensive enlargement, in 1847, widened the canal to thirty-two feet and deepened it to six feet. Substantial changes were also made to the locks and aqueducts. With this enlargement, boats ninety feet long, fourteen and a half feet wide, and carrying 140 tons of coal could ply the canal. In the late 1800’s, these ninety-foot boats cost the canallers $1,800. Weigh locks, one at Hawley and one at Eddyville, were used to weigh boats to determine the tonnage of goods carried, which the canaller would be paid for hauling.

Canal boats were simple structures. The stern, or back of the boat, was where the cabin was located and where the people who operated the canal boat slept and ate. The goods being hauled were carried in the center portion of the boat, and at the bow, or front of the boat, there was room for storage and a place to keep feed for the mules or horses. In the canal’s peak years, thousands of boats plied the canal at any one time. Slowly but surely, the usefulness of the canal waned due to competition with railroads. Determined by the canal company, the number of boats in the final years was only in the hundreds. In 1898, the last year the canal was officially opened, there were only 200 coal carrying boats in operation.

Life on the Canal

The canal company required that each canal boat have at least three people working it, a captain who owned the boat and was responsible for all operations, a bowman to steer the boat, and a driver or towboy/girl to walk with the mules on the towpath. Many times the bowman was the captain’s wife, and his children acted as the drivers. If there were no children, a child could be hired, for which they sometimes received $4.50 a month, plus room and board.

The towboys or towgirls walked fifteen to twenty miles a day with the mules on the towpath, regardless of weather conditions, from April to December, six days a week. When not walking on the towpath, the towboy/girl’s responsibilities also included feeding, watering, and caring for the mules, and sometimes they also operated the bilge pump, which was hard and exhausting labor. Many children employed were homeless orphans from charitable institutions in New York City. For the most part, they were at the mercy of the captain.

While many towboys/girls had difficult lives working on the canal, those who drove for their fathers recalled that the canallers would play with them and that they had fun riding the horses that pulled the boat. Some would try to keep up with their studies as they rode the mules or horses. Unfortunately, most canal children only went to school during the two or three months in the winter when the canal closed and were not well educated.

Very young children were tied to the boats to prevent them from falling in the canal. Many times children playing on the boat or along the towpath fell in the canal and drowned. The boat’s cabin, about eight feet by ten feet, was where the crew lived, ate and slept. It included bunk beds, dish closet, stove, and drop leaf table. Curtains at the windows, flowers, and plants usually meant that there was a woman aboard. If there wasn’t, the driver usually cooked, scrubbed the floors and killed the bed bugs. Many boatmen would offer travelers free food and lodging in exchange for some company and a helping hand around the boat.

Short Link: